Botanic Ridge residents are urging Casey Council to solve a local rabbit plague after several years of exhausting and futile battles with the invasive species.

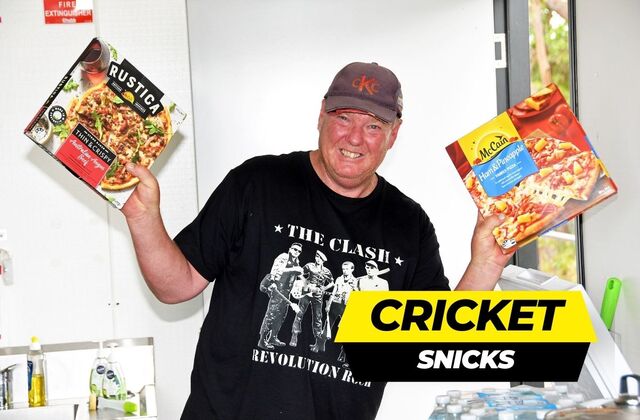

Richard Francis, president of the Vertebrate Pest Management Association of Australia and a zoologist who works to remove rabbits in the Casey area, removed 100 of them on one night a week ago.

“Still, you can’t tell any difference,” he said.

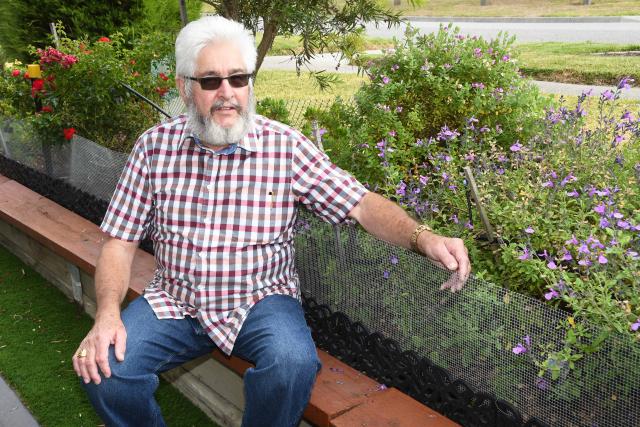

Resident Merv McCormack said the area was just crawling with rabbits in the early morning and at sunset.

“They’re eating our roses, thorns and all. They’ve ruined a couple of my garden beds. We’ve had to take extra caution of putting barricades around our gates,” he said.

“They dig under everywhere. I put up plastic mesh, and they just eat it and make a hole and go through.

“It cost me a fortune in star pickets, and they just crash from the front yard. You look at the house and all you see is bloody star pickets.”

When Mr McCormack moved in about a decade ago, the area was all farmland and there were no issues with rabbits.

“They had all their burrows in the farmlands and were quite content,” he said.

“But with all the development and subdivision in the area, they’re being forced out of where their natural habitat was.

“All that area that the rabbits were quite happy in is not available to them. They just go roaming around everywhere.”

Mr Francis said a combination of productive agricultural land and the sand dune systems around Cranbourne and Botanic Ridge contributed to ideal conditions for rabbits to breed.

“Rabbits like to create warrens and these old tertiary dunes are ideal for them to burrow in, and then you’ve got the low-lying alluvial areas with nice vegetation to feed on,” he said.

“Rabbits have a very high reproductive rate. But they still need a safe place to sleep and to breathe, and they still need to have access to food. And in Cranbourne, they’ve got all those things very close by.”

Mr Francis said there were limited methods that could be used to deal with rabbits in the area because of the existence of an endangered species called the Southern Brown Bandicoot.

The bandicoot was assessed as endangered in the 2021 Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act Threatened List Victoria.

A key population of the species lives at and around the Cranbourne Royal Botanic Gardens.

“There’s a reluctance to bait rabbits in case bandicoots are also affected by the baiting,” Mr Francis said.

“There’s no actual evidence that the bandicoots are affected, but as a precaution, baiting is not used in areas where there are Southern Brown Bandicoots.”

Fumigation, warren destruction, and shooting are the techniques used in the area to remove rabbits, according to Mr Francis.

Fencing is also an option, but it is not used widely as it also affects the bandicoots and stops them from moving and dispersing.

In 2016, Cranbourne South was one of the parts of Melbourne to trial test the RHDV1 K5 virus that targeted feral rabbits.

When asked about the efficacy of the new virus, Mr Francis said it did not go well in areas where breeding was quite constant.

“In order for the virus to work, there needs to be a period of time where rabbits aren’t breeding, and they need to get exposed to it during that time,” he said.

“It works very well in dry areas. If you go more inland Australia where breeding only happens at particular times of the year, then the virus has worked quite well there.

“They breed almost constantly in the Cranbourne area because the environment is mild and there’s always enough food.”

Drought years were a different story, but Melbourne already had two mild summers in a row, two years of what would be called mild conditions where rabbits have been breeding continuously, Mr Francis said.

When Mr McCormack realised individual efforts would not be able to cope with rabbits in June 2023, he went straight to Casey Council.

He claimed the council advised him to contact the Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA).

The council helped him contact the EPA and one EPA officer visited the site in the same month and advised him to contact the Department of Agriculture, Victoria.

Mr McCormack said he heard back from the department eight months later.

Ultimately, though, rabbits fall under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 as an established pest animal and it is individual landowners who have an obligation to prevent the spread of, and as far as possible, eradicate rabbits from their land.

According to their website, effective rabbit control requires an integrated approach using a combination of control measures and it is important to work with neighbours, rather than individual properties. It also says you can talk to neighbours – and your local Landcare group – about forming a cooridinated plan.

“Good planning is essential for maximising the effectiveness of your rabbit control program, while minimising impact on other animals. Consider rabbit density, distribution and habitat as this will determine what actions are appropriate,“ their website says.

Some gardeners use blood and bone to deter rabits, and chicken wire – but ensure it’s buried into the ground.

When inquired, Casey Council said they were aware that rabbit numbers were currently high in Casey and across Victoria more broadly, which was due to increased food availability from two-to-three years of high rainfall which had triggered ideal conditions for breeding.

“To manage rabbits in Botanic Ridge, the City of Casey has mapped warrens throughout the park network and a contractor has been engaged to deliver on-ground rabbit control works, with works scheduled to commence in early March 2024,” a spokesperson said.

“The presence of the EPBC Act listed (endangered) Southern Brown Bandicoot in the Botanic Ridge area limits the use of other control methods such as Pindone. Similarly, the use of 1080 baiting is constrained by the presence of domestic dogs in the Botanic Ridge area.

“The City of Casey is also working with Agriculture Victoria to notify private landowners of their obligations to control rabbits.”

Mr McCormack said people needed to keep following up on the rabbit plague, otherwise no change would happen.