At dawn vigils and mid-morning services around all parts of this country on Monday – from major cities to rural hamlets – we stopped to listen and reflect on what it means to live up to, and die for, a set of ideals.

Anzac Day speakers talked variously of ‘mateship’ and courage, of tactics and trench warfare, of aerial feats and naval skirmishes, and of service and sacrifice.

The speakers may have honed in on one Digger, or a group of mates, or a company, a battalion, a flight crew or a ship’s company.

They may have alluded to some of the bigger themes that we hold – or should hold – dear: Freedom, justice, opposing tyranny in all its forms and ultimately of peace.

And all the while, we sit or stand dutifully – we who were brought up in the safety and security of one of the world’s few enduring stable democracies.

We may shuffle and lean this way and that to relieve aching feet or twinging joints, but we are still and silent as their names are mentioned and their service recalled.

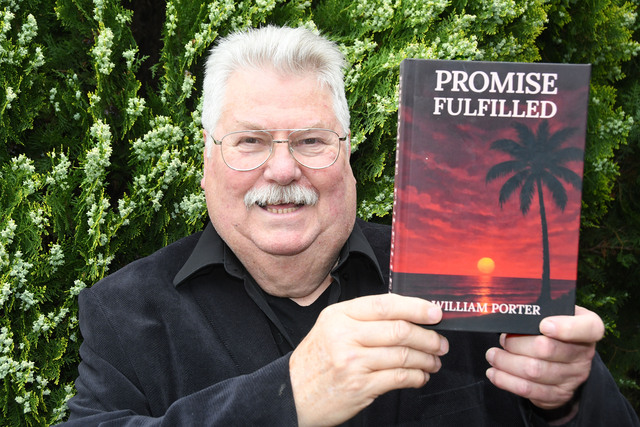

And in doing so, we uphold a promise made to those young men and women who march off in service to this country.

It’s a tacit rather than an acknowledged promise.

And it is simply this: That, should they perish, their supreme sacrifice will never be forgotten. That should they return, though indelibly changed, their service will never be forgotten.

We acknowledge at this time and in this way that the cause they fought for was important, and that their lives and their sacrifices didn’t amount to nothing.

Australia is a small country in global terms, but has a strong record of military service.

Unlike other countries, we don’t use our armed forced against our own people or our neighbours.

Although not spoiling for a fight, we recognise that sometimes it is the lesser of two evils – that some causes are worth fighting for – and that, though peace is preferable, some fights are forced upon us.

We, and our like-minded partners and allies, demonstrate that we will stand for the cause of freedom, that we will fight for the cause of justice.

But such a stance comes dearly – for at the pointy end of a cause like freedom are the lives of our sons and daughters.

No sane person would risk the flower of our youth in a wasteful cause.

But, sadly, the world has never been closer to armed conflict since World War II.

It seems we’re bristling with new weapons and the world has fallen into the grip of a new arms race. Australia’s new capabilities with nuclear submarines, a space command and newly announced research into hyper-sonic weapons are in part a symptom of those larger tensions.

In every generation, it seems, there is someone like Attila or Napoleon, Adolf for Saddam, Osama or Vladimir, who must demonstrate a sense of superiority – not by some high achievement – but by beating down those around him. A vicious willfulness that writes its claims to ‘greatness’ in the blood of others.

And while those people exist, our youth – our very way of life – will always be at risk, for that willfulness must not be permitted to prevail.

There’s an old joke – it’s not until a man has a mosquito land on his testicles that he discovers that difficult situations can be dealt with without resorting to violence.

The tyrant must also learn this lesson – that in lashing out, he will hurt the things he wishes to protect most.

And for those who march out to teach the tyrant this lesson, we hold this promise – we will remember – lest we, too, are forced to forget what it’s like to live with the luxuries of peace and choice and liberty.

Our democracy, our way of life, is a fragile thing – no less fragile than the lives that have defended it.

We enjoy it and hold it dearly, for it has come at the cost of those we have held most dearly.

And, for this, we will never forget.